Well, here it is! The long-awaited, long-overdue and just plain long Lost Turntable Guide to Recording Vinyl.

What took so long? (And why is it so damn long?)

Well, what I thought was going to be a quick cut-and-dry “how to” guide slowly began to morph, mutate and altogether spin out of control. When I first started writing this thing I thought it was just going to be nothing more than some tips and tricks on recording records. But then I decided I should expand it to be a more conclusive guide covering the entire vinyl ripping process, but once I got there I realized that I had include sections on hardware and software too…

So yeah, things kind of got out of hand. But here it is! Split into four convienent and hopefully easy-to-understand chapters.

Chapter one deals strictly with hardware. Turntable, pre-amps, cartridges. I go over my recommendations and what I think you should look for when choosing gear.

Chapter two is all about software, the recording and restoration software that I think is must-have if you want to do this right.

Chapter three is an in-depth step-by-step guide showing what I do when I record vinyl. It’s only 100% applicable if you’re using the exact same equipment and software as I am, but even if you’re not it should help you out a bit.

And finally chapter four is where I offer some tips, tricks and links that didn’t fit anywhere else.

So without further ado…an introduction.

Introductions and Disclaimers

Before I really get going, there are two things I want to get out of the way.

First, I’ve been recording vinyl for six years now. I learned as I went, making a ton of mistakes along the way. And I’m fairly certain I’m not done making mistakes. So if at anytime during this guide you think I’m full of it, or doing something horribly wrong, I very well might be. Let me know! Just don’t be a jerk about it. I’m always looking for ways to make my rips better, so any polite and constructive criticism is welcome.

Second, this is not a guide on how to record vinyl “on the cheap” or “fast and easy.” This is a guide on how to record vinyl properly, with high-quality results that are worthy of being in your MP3 collection. You can’t do that quickly, easily, or inexpensively. Not including my computer, my final cost for my set-up, which includes my turntable, cartridge, pre-amp and recording/restoration software cost me over $600, and that’s substantially cheaper than what many “audiophiles” pay for their set-ups. It sucks, but this isn’t an endeavor for those who aren’t willing to spend a bit of cash. Sorry.

Okay, now that I have that stuff out of the way…let’s do this!

Chapter 1 – Hardware

Turntables

This part is pretty important, so you might want to take notes.

If you ask me, there’s only one turntable in the world worth getting (more on it in a bit). However, I realize that not everyone has the same tastes as me, so before I offer my singular recommendation, let me extend a few general tips you should keep in mind when picking a deck.

First of all, always avoid USB turntables. Almost all of them are abominations that can neither effectively play nor record vinyl.

Why?

First of all, most use ceramic needles. In addition to sounding horrible, these things destroy records. They’re outdated garbage, keep them away from your vinyl.

Secondly, many use built-in pre-amps (a pre-amp boosts your phono signal so it can be heard properly), and those just don’t cut it when it comes to sound quality. Your music will sound muffled, muddled and altogether bad. Whenever I go back to recordings I made using my old ION USB turntable, I can’t believe how hideous they sound. It’s like they were recorded underwater.

Finally, recording straight from a turntable to your computer via a USB port isn’t as easy as it might seem. You’ll get a lot of interference from the electronics in the turntable, and the process itself takes a lot out of your computer’s resources. It’s just not worth the hassle.  Get a real turntable, you can hook it up to your PC with little effort.

With that out of the way, the biggest decision you’ll have to make when choosing a turntable is whether you want a  belt-drive or direct-drive model.

With a belt-drive turntable, the motor is connected to a belt, which in turn is connected to the platter. The motor spins the belt, and the belt spins the platter. On a direct-drive turntable, the motor is connected directly to the platter (typically underneath), spinning it directly.

Which usually sounds better? It’s a contentious subject. Some believe that direct-drive turntables can create a noticeable “hum” in your recordings. Â Others, myself included, don’t like belt-drive tables because they don’t always spin at the right speed. Belts wear down over time, and a worn down belt will cause your turntable to spin too fast (audiophiles call this “flutter”). It’s the kind of thing that you never notice at first, it only comes to your attention after you’ve recorded half-a-dozen records at slightly the wrong speed. It can be maddening.

On the other hand, I’ve never heard any noticeable “hum” coming from any medium-to-high-end direct-drive turntable I’ve owned, and they always spin at precisely the right speed. I’ve been told that super-high-end belt-drive decks, ones that cost upwards of a grand, don’t have problems with flutter, but I’ve never wanted to spend enough money to find out. I would recommend a direct-drive deck, for ripping vinyl it’s almost always a safer bet. In fact I would recommend one direct-drive turntable in particular, the  Technics SL-1200.

In all honesty, if you want a turntable that sounds great, runs great and even looks pretty damn great, then just get a Technics. There’s a reason why nearly every turntable on the market today is trying to emulate the look and feel of the Technics SL-1200. It’s because they’re some of the best turntables ever made. Sadly, Panasonic shut down production of the Technics line a few years ago, so you probably won’t be able to find a new one at a fair price. Don’t let that stop you though, since the Technics 1200 was one of the most popular turntables of all time, you can usually find one used online for less than $300 if you know where to look online. I picked one up on Craigslist for $300 and it was worth every penny.

Cartridges

While I have no problem recommending just one turntable, I can’t do the same with cartridges. There are just too many out there that it’s impossible for to keep track. The best advice I can give you when choosing a cartridge is to do your research. Different cartridges work better with different turntables. So go to Google and search for something like “best cartridge for [turntable model]” and see what comes up. Check out AudioKarma, that’s my go to message board for this stuff (although most people there will tell you that direct-drive decks are the devil). The audiophile message board nerds who talk about this stuff are usually good sources. Just don’t spend over $150-$200 for a cartridge if you’re just getting into vinyl, you should be able to find a decent one for between $70-$100.

Me personally, I play all my records using a Nagaoka MP-110 cartridge. From everything I’ve read, it comes highly rated for Technics SL-1200 turntables, and is fairly priced at around $100. Of all the cartridges I’ve used it has the best stereo separation and the best tracking; it also doesn’t amplify bass or polish the audio in anyway, it just plays the records accurately and beautifully.

Conversely, I recommend you avoid the Ortofon Arkiv (lousy tracking, too sensitive), DarkHorse Sanyo (horrible all around) and the Stanton Groovemaster (too damn heavy and loud). But once again, that only goes for the Technics SL-1200 and for recording vinyl, results may vary with other kinds of turntables.

No matter what cartridge you end up going with, I suggest buying it from The Needle Doctor, the best site for turntable supplies on the Internet.

102/24/13 Update

While I still recommend the Nagoka MP-110 for most systems, I recently discovered that for whatever reason, the cartridge did not play nice with my new computer. I don’t know why and I can’t explain it, but for some reason when I upgraded my computer all my recordings became muddled. When I replaced my cartridge with another model, the problem disappeared!

If you find yourself with this problem, then I recommend the Audio Technica 120E/T. It’s also about $100, and gives a sound that is nearly identical to how the MP-110 used to sound on my system.

Pre-amp/Soundcard

Often overlooked, a phono pre-amp is a vital part of any turntable system. These special amplifiers are made with turntables in mind, and raise the levels of a turntable signal to the proper volume/EQ settings that make it possible for you to hear your records at a comfortable volume. If your turntable doesn’t have an internal pre-amp (and it shouldn’t, those suck) you will need a pre-amp in order to listen to and record your LPs.

In addition to a pre-amp, you’ll also probably need an external soundcard, unless your internal card has a line-input. And even if it does, it’s still not a bad idea to get an external soundcard. Most internal cards just aren’t cut out for recording from a line signal. It’s hard to explain, and I don’t entirely understand it, but I was never happy with the results whenever I tried to record vinyl using my internal soundcard. Everything always sounded like half the treble was missing.

Fortunately, you don’t need to buy both an external soundcard and a pre-amp, as there are a lot of pre-amps made today that function as both. I’ve used a few, and the one I’ve gotten the best results with is the  ART USB PhonoPlus v2 Computer Audio Interface.

This thing is a godsend. It requires no drivers, has optional built-in hum removal (great for tape recording or if your system has a lot of R/F interference) and it only takes a few minutes to set up (which I’ll get to in another section). I really cannot recommend this thing enough, nor can I say enough good things about it.

Conversely, I can’t say enough bad things about any external soundcard made by M-Audio. While these guys make great professional-grade (translation: incredibly expensive) hardware, their entry-level stuff consistently proved itself to be completely worthless to me. It never works right, requires a ridiculous amount of drivers, and it even crashed my system to the point where I had to re-install Windows 7. If you have a choice between an M-Audio soundcard and getting punched in the gut, I recommend the gutpunch.

…moving on.

Chapter  2 – Software

Recording/Basic Editing Software

There are a lot of ways to go here. Some people really like Audacity, and it’s really hard to argue with free and open-source…unless you’re me.

I’m not a fan of that program, I find it clunky, hard to understand, and needlessly complicated. It’s also a resource hog and slows down my system whenever I’m working with it. I avoid it. My own personal preference for recording and basic editing software is Sony Sound Forge Audio Studio. It’s probably a little over-powered for what I do, but it works, it doesn’t slow down my system, and it’s easy to use. Those are three very big selling points for me. It’s also great for whenever I do want to do something a little more complicated with my audio files, such as adjusting the EQ settings or fiddling with the playback speed.

Sony Sound Forge Audio Studio also gets a ton of little things right. It’s ultra-versatile, allowing you to record in quality as high as 32-bit/192,000 Hz audio, and you can save in just about any format you could desire, including WAV, MP3, FLAC and even OGG. It also allows you to zoom in and out of an audio file by using your mouse’s scroll wheel (something Audacity cannot do), which is incredibly handy when removing pops and cracks from a recording. It’s also very efficient and fast, I can edit and save a file in Sound Forge in about half the time it takes me to do so in Audacity. So, yeah, it might not be free, but my time is worth the money.

Click Removal

No matter how good your system, no matter how clean your records, you will hear the occasional snap, crackle or pop in your recordings. There’s nothing you can do about it. However, you can remove most of them with the help of the right click removal software. Ever since vinyl has come back a ton of programs have appeared on the market claiming to be able to restore even the most haggard of records to near-CD quality. For the most part, these programs are hogwash. Either they don’t remove enough of the clicks and pops, or they remove all of them at the expense of the overall fidelity of your music.

To date, I have only found one program that can easily remove most pops and clicks from a recording while not affecting the quality of the recording. That program is ClickRepair. Setting it up can be a bit of a bother (I’ll get to in my next section), but once you figure out how it works it can be a real life saver. ClickRepair has saved recordings that I thought were lost causes. It costs $45, but it’s totally worth it in my opinion.. But if you’re hesitant to spend the dough without giving it a test drive, a trial version is available at the official website as well.

Hum/Noise Removal

Sometimes when you’re listening to vinly you might pick up a kind of hum or hiss that’s omnipresent over your entire recording. Typically it’s radio frequency (R/F) interference. If you have a decent turntable and pre-amp, then you shouldn’t be having this problem. Before you go the software route, try moving your equipment around; hook it up to a different power outlet; or try some different cables.

However, not all hiss and hum is caused by R/F interference, some records are just naturally noisy. It can be especially annoying if the music on the album is quiet (Tangerine Dream albums have this problem far too often). If that’s the case, then you might have to go the software route to scrub your recordings free of hum and hiss. One program I’ve found that can do this pretty well is the iZotope Music and Speech Cleaner. While it doesn’t work miracles, it does a good job of removing these incredibly annoying noises on exceptionally quiet records. Like ClickRepair, iZotope’s Music and Speech Cleaner isn’t free, but there is a trial version available for you to check out before you shell out the bucks.

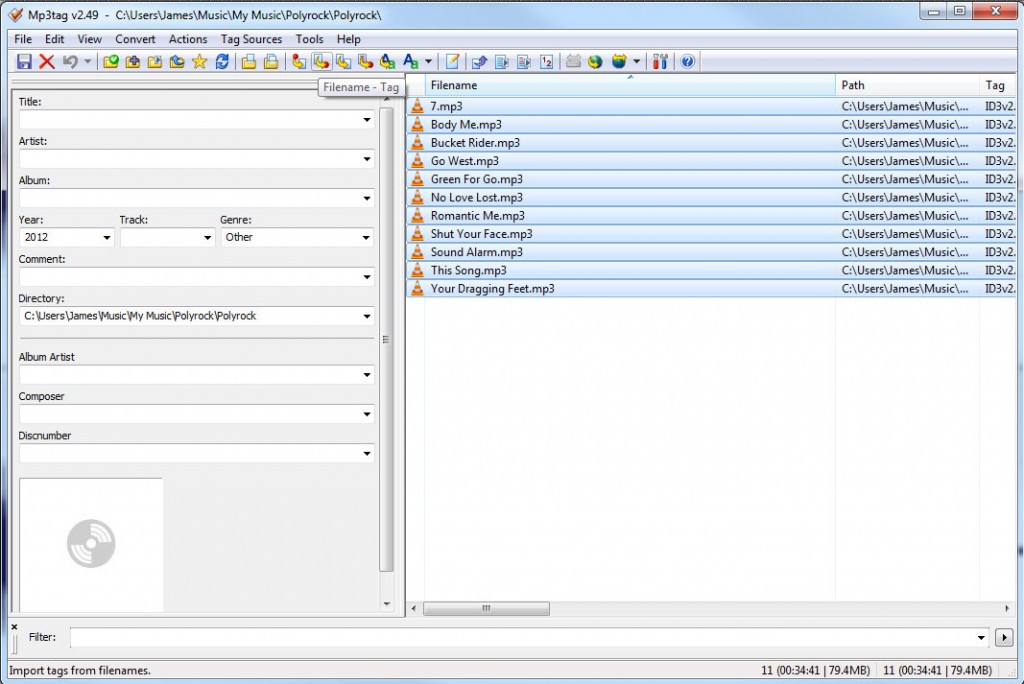

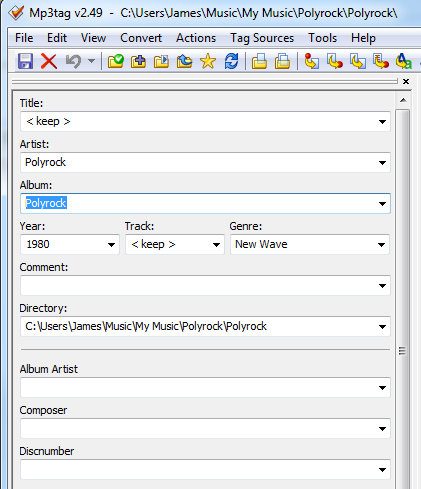

ID3 Tagging

ID3 tags are metadata on an MP3 file that tell you the name of the track, what album it’s from, the artist and so on. For years, I just used iTunes for this, until I discovered that for some reason iTunes does not like creating ID3 tags for songs I ripped from vinyl. Why? I have no idea. But whenever I had to rebuild my library, any ID3 tag I created in iTunes came out broken, song titles would vanish, genres would change, it was a mess. Now, the only thing I use iTunes for is to number the tracks after I give them ID3 tags.

For everything else I use MP3Tag. It’s free, works like a charm, and has a ton of batch editing features that make tagging large groups of files a breeze. I love it.

Okay, now that you know what hardware and software I use, it’s time for me to show you how I use it!

Chapter 3 – The Walkthrough

As I said before, this walkthrough only details how I do this using my equipment and nothing else. That’s all I know, so that’s all I can give. If you want help with other kinds of pre-amps, turntables or software, I can’t help you. Sorry.

So let’s get started.

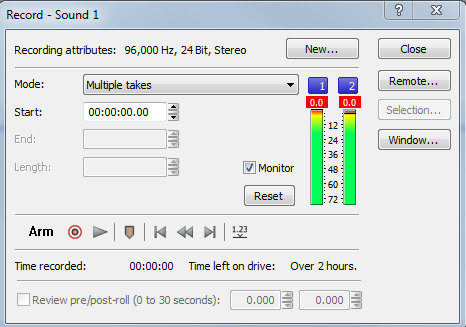

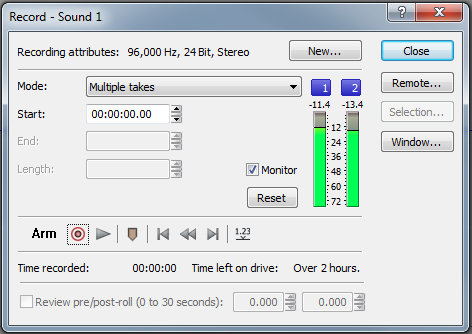

As I said before, I do all my recording on Sony Sound Forge, but before I commit to a recording, I make sure all my setting are accurate. To do this, I start a recording that I will not save, and drop the needle somewhere in the middle of the record. I try to find an especially loud part to check the levels.

Red is bad, that means my levels are too high, which will lead to clipping and distorted sound. I have to go into Windows’ audio settings and make some minor adjustments.

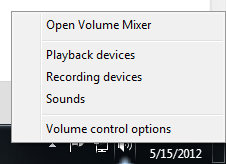

To do this, I right-click on the speaker in the task-bar and select “Recording Devices” from the pop-up menu that appears.

Next up, I make sure that my pre-amp isn’t doing some clipping of it’s own. The ART V2 has gain controls on it, complete with a monitoring light that tells you if the gain is too high. While I rarely need to adjust my Windows volume settings, I often have to change my gain settings on my pre-amp, as some records can be much quieter than others. You always want to have as much gain as possible without the signal going into the red, this cuts down on hiss and other line noise that can be a real pain to get rid of later.

To make sure the pre-amp is set up right, I once again drop the needle on a loud section of the record and look at the signal light. I adjust the gain settings until it is as loud as it can be without the signal going into the red.

Green is good! Most albums are fine with a gain of around -2, but for some quieter albums I crank it up a bit.

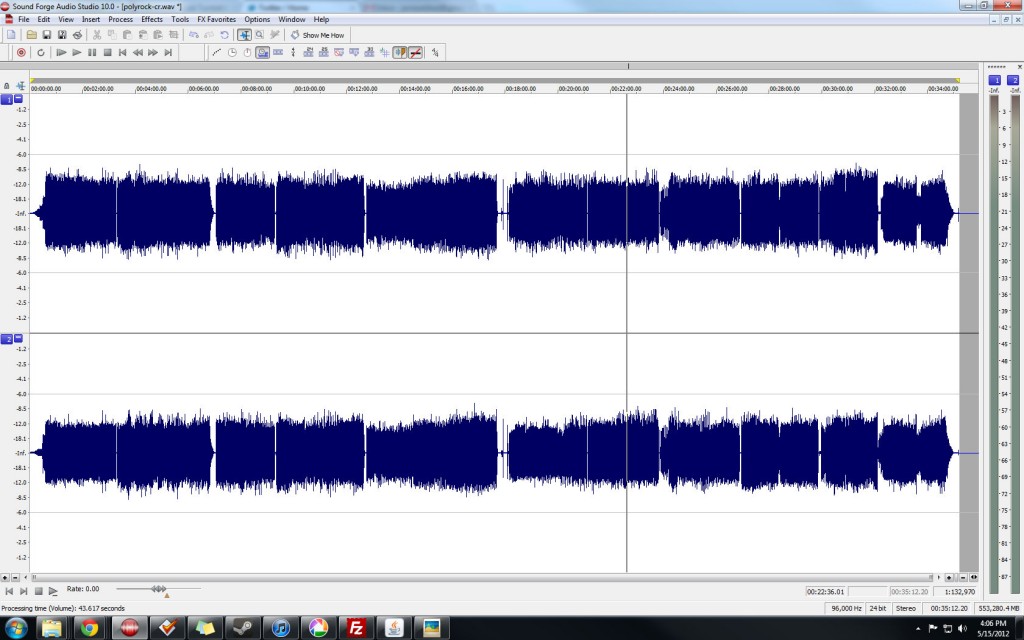

After that’s all set, I can move onto actually recording and listening to my record, which for the purposes of this example will be Polyrock’s 1980 self-titled debut.

I usually record one record at a time. Some people will stop a recording after each side as to keep the size of the audio files down. I usually don’t find that necessary, but whatever floats your boat is fine.

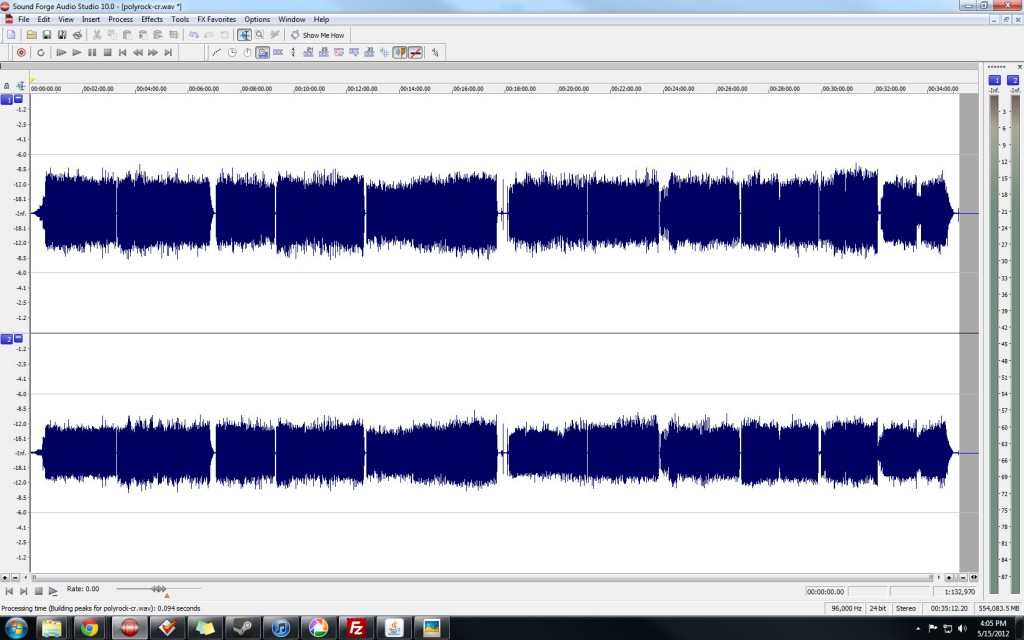

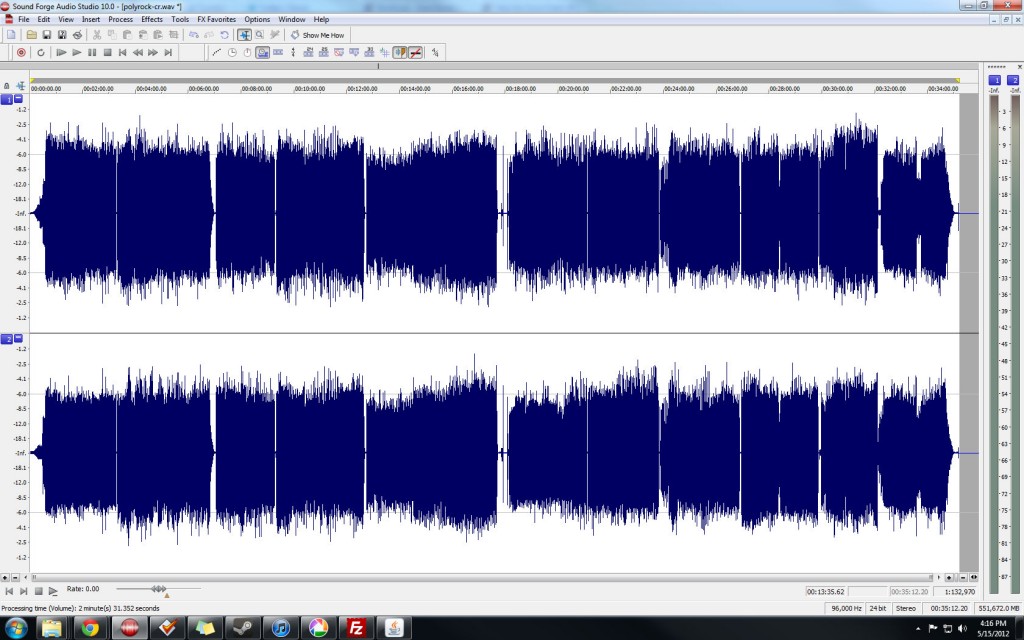

After I’m done recording the album I hit stop in Sound Forge, and I’m presented with a waveform of the album.

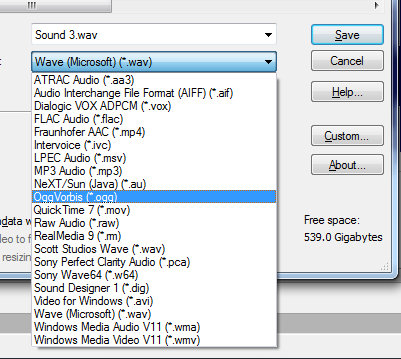

Now, before I do anything I save it as a WAV file. Most sound editing programs like ClickRepair can only read WAV files, so its best to save them in that format. I don’t convert my recordings to MP3 until I’m done doing everything else.

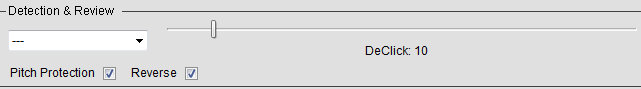

After I save the file as a WAV I open it in ClickRepair to clean it up a bit. ClickRepair is an amazing program that can work wonders, but not at the default settings. For ClickRepair to work right, without any noticeable distortion or unwanted sound removal, I always tone it down a bit by adjusting the following settings, which were suggested to me from Paul at Burning The Ground:

Then I run ClickRepair on auto. Some people use it manually, but honestly, I don’t know how, and even if I did, that seems like it would take forever.

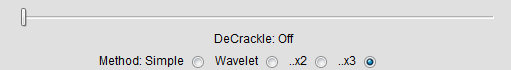

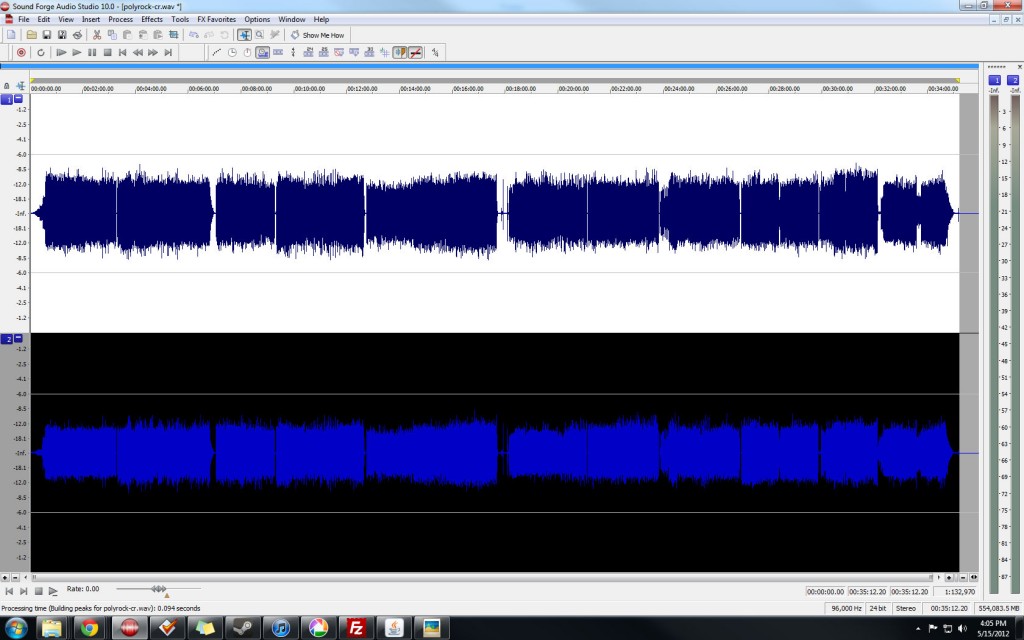

ClickRepair doesn’t overwrite the original file, instead it saves a copy with a “CR” suffix added to the file name. After it’s done running, I open that file, along with the original, in Sound Forge and compare them. If I see any major differences between the files’ waveforms, I listen to compare and make sure no music has been removed along with the clicks. I would say that 99 times out of a 100, there are no problems. But if I’m recording drum and bass, glitch (obivously) or anything that actually incorporates the sound of a record click into the song, then ClickRepair might have a problem with it. In those cases, I usually go back to the original file and manually edit it. It’s actually easier than it sounds. All I do is zoom in until I am able to highlight the defect and nothing else and then I just delete it. These clicks are usually less than a tenth of a second long. I don’t lose any music when I delete them, just the defect.

(If there’s any hum or hiss in the recording, this is when I go into iZotope to try and fix that. Since that program is 100% idiot-proof, and I almost never use it, I’m not going to go into that.)

Now the file is declicked to the best of my ability, but there’s one problem left I need to tend to.

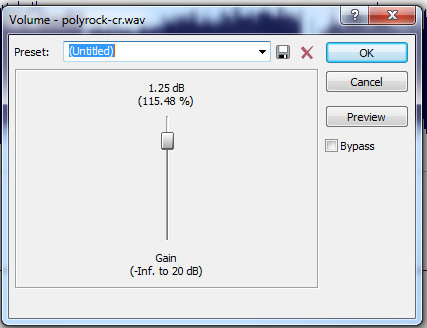

If you look closely, you may notice that the right audio channel is just a hair quieter than the left channel. This is a problem that I’ve run into with many turntables and cartridges over the years. Truth be told, it’s not much of an issue. The difference between the volumes is actually barely noticeable, if at all. However, since it is a fixable problem, I usually take care of it. While the difference in volume can vary from album to album, I’ve found that a volume of change 115% usually takes care of it. This is how I take care of that:

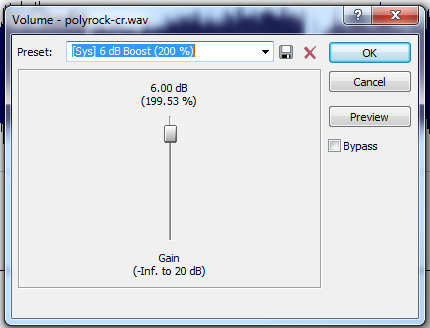

Then I go to “Process” and then “Volume” to open up this menu. I adjust the bar so it’s increasing the volume by 1.25 dB (115%).

It’s never perfect, but it’s usually good enough,and your ear won’t be able to tell the difference anyways.

Now to make one more volume change. While there’s nothing wrong with the recording as it stands now, it’s a little too quiet, especially when you compare it to newer songs, which are far too loud. While I don’t want to equalize my recordings to match the over-compressed volume of those new recordings, it wouldn’t hurt to boost them a bit by going back into the volume adjustment settings.

Now that reocrding has been cleaned and adjusted to the best of my ability, it’s time for me to cut it up into individual tracks by selecting them one at a time; pressing “CTRL+X” to cut them out of the audio file; opening a new audio file; and then pressing “CTRL+V” to paste the song into that new file. Then I save the file.

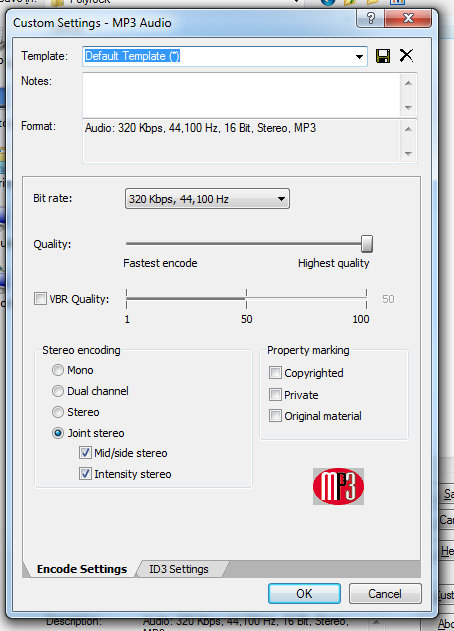

I’m old school and stick with MP3s, but if you’re super-concerned with audio quality, then you can always go FLAC. As far as my MP3 settings go, I always save at 320Kpbs and at 44,1000 Hz. I’m sure some audiophiles out there are screaming at me right now, but I’ve tried higher sample rates and other formats, I honestly couldn’t hear a difference. Sound Forge also lets you choose encoding speed. Go for quality over speed every time.

My custom MP3 encoding settings. I’ve never heard a difference between Joint and regular stereo, so don’t ask me about it.

When I save the songs, I make sure that I save them in the proper directory in my iTunes library (artist name/album name). As far as file names go, I just name them the title of the song. This comes in handy for the next step, editing the files’ ID3 tags.

As I said before, I do all my tagging in MP3Tag. I love its interface. After I drag the songs I want to tag into the program window, Â I just have to do the following:

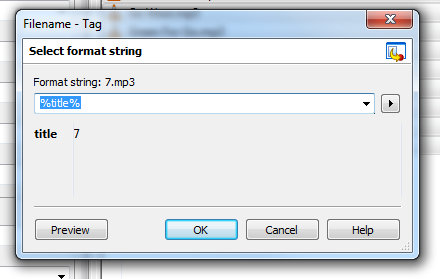

The “filename – tag” button creates an ID3 tag based on the filename. Since my filenames are the song titles, I just set the parameter “%title%” and it fills in the title field with the filename.

MP3TAG is kind of a pain when it comes to track numbers, so I do that part in iTunes, after I’ve imported them into my library. And in case you’re wondering, I import my tracks into iTunes by creating a new playlist and dragging the songs into it. From there I can go into the song information, add track numbers, and make any other minor adjustments might be needed.

And that’s it! I now have my album recording, cleaned up, converted and tagged, ready for listening. Recording time not included, it usually takes me about 15-20 per LP, with 12″ singles and 45s taking no more than 10 minutes. Of course there are always exceptions to the rule, some albums are so scratchy that I have to clean them manually, and if a record has a skip in it that’s a whole other beast. But for the most part it’s not that time-consuming, it only becomes a chore when I let 20 recordings sit on my hard drive for a week and I have to plow through them all in one sitting. Â Even then, I find the process oddly soothing, like its something I can do to shut my brain off from the outside world and just zone out on for a bit.

Chapter 4 – Addendum/Tips

Properly Set Up Your Turntable

You could have a $100,000 turntable with a $10,000 cartridge, but it will all be for naught if you don’t set it up right. I almost wrote a guide for this as well, but there are a ton of them on the Internet already. Here’s a good one that should explain everything you need to know.

Clean Your Records!

If you’re buying used records, then you need to do your cartridge a favor and clean those bad boys before you plop them on your turntable. A record may look clean, but there could be boundless amounts of gunk, dirt, dust and grime hidden in its grooves. Not only does all that make your recordings sound worse, but it can even damage your records. You want to clean your records, and the best way to do that is with some sort of record-cleaning machine.  A lot of people recommend high-end motor-powered machines that can cost hundreds of dollars, but I don’t think you need to go that crazy. I use the Spin Clean Record Cleaner. It’s only $80, and it works wonders. You can find out more about it on their official website.

Some Records Just Sound Horrible

Vinyl is a physical medium, and with that comes physical flaws that cannot always be avoided or fixed. Scratches, warps and other signs of wear and tear are a way of life when you’re buying used records. But don’t assume that all new records are going to be flawless either. For example, I have never heard a 12″ single of the Eurythmics “Right By Your Side” that didn’t sound mis-pressed; I have three copies of the single to Michael Jackson’s “Moonwalker” that all skip in the exact same place; and my copy of The Chemistry of Common Life by Fucked Up came with a loud pop on the title track.

It sucks, but these things happen. Learn to live with them, fix them when you can, and don’t let your head explode worrying about them. Trust me. It’s for the best.

Don’t Get Discouraged!

This is probably the most important piece of advice I can offer. If you really want to record your records and you’re having a lot of problems getting everything to sound right – don’t give up! It took me years to really get my act together when it came to recording vinyl, and I’m still learning stuff every time I check out an audiophile message board or visit other MP3 blogs who do the same thing I do. Just keep at it, and you’ll get better!

And if you really love your music and the sound of vinyl, it’s totally worth it.

I’m sure he did and the only thing worse than bad spelling are people who are overly pedantic.

Just came across this guide as i’m currently building my recording set up. At the moment i’ve a numark tt200 and a very basic riaa pre-amp. Next on my list is a focusrite scarlett 2i2 and ortofon 2m red. I was wondering how important having a good pre amp is, doesn’t look like i’ll get that answer here but hopefully..

I’ve been manually removing pops and crackles with soundforge. Using the click and crackle removal tool for areas with lots of little tics, the kind that sound like burning twigs on a camp fire. But with the large singular snaps and pops i’ll zoom all the way in and they are usually in either the left or right channel only. You mentioned deleting the few microseconds of audio but what i do is highlight the click in which ever channel it is in and then use tools>repair>copy other channel (this can be repeated if it does not copy the other channel quite enough). So you get a few microseconds of clean audio in it’s place instead.

The best reasonably priced (and much better than any of the free programs out there) pop and click remover is by far: Click Repair (http://www.clickrepair.net). I usually use it at 20% for recordings with light pops and the default setting (50%) for recordings with a lot of noise. I have even cleaned up pretty noisy self-made 78 RPM recordings from the 40’s making them more listenable. When you buy a license it is good for one person, but you can put on any of your computers. If I have a really stubborn pop, I will expand the waveform in Audacity or Wavosaur and remove it manually. He offers a Denoise program also. Used that once (the trial) to remove hum from an old jazz recording.

Yeah, I say most of this in the article you’re commenting on but didn’t read entirely.

Yes, I have previously read your entire article. I am enthusiastic about this program, that’s all. Done with this site, no need for venim.

And it is $40, not $45.

Excellent article. Thank you for sharing your accumulated knowledge over the years. Can you please give some details about the problem with Nagoka MP-110 and your new computer? I am currently using Ortofon Arkiv on SL-1200 and I have the same experience as you, lousy tracking, too sensitive on bad elements of the record. My pre-amp is the Pro-ject Phono Box USB V and my computer iMac.

Great article!! I have sound forge 9.0 and am converting my vinyl but am finding that the tracks are not seperating properly and am having difficulty editing them in sound forge, any suggestions?

I’m afraid you’ll have to go into more detail. I separate them all manually.

For your info and to help, I have a Stanton ST.150 with a Shure Whitelabel cartridge to play the vinyl records, then an ART UBS Phono Plus Preamp to convert from Phono output to Line level, and on my computer I use a software called Goldwave to record & edit the final tracks… I record one song at the time… always… Regards, dlx 😉