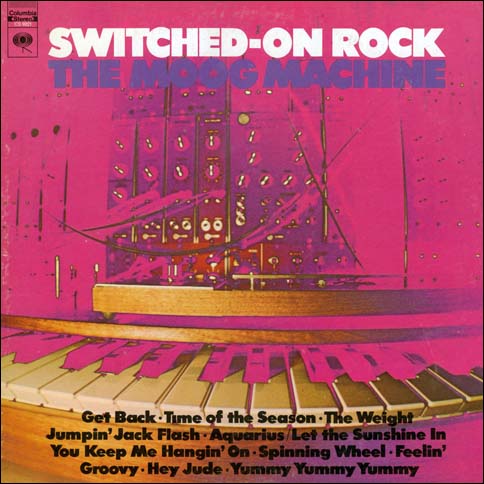

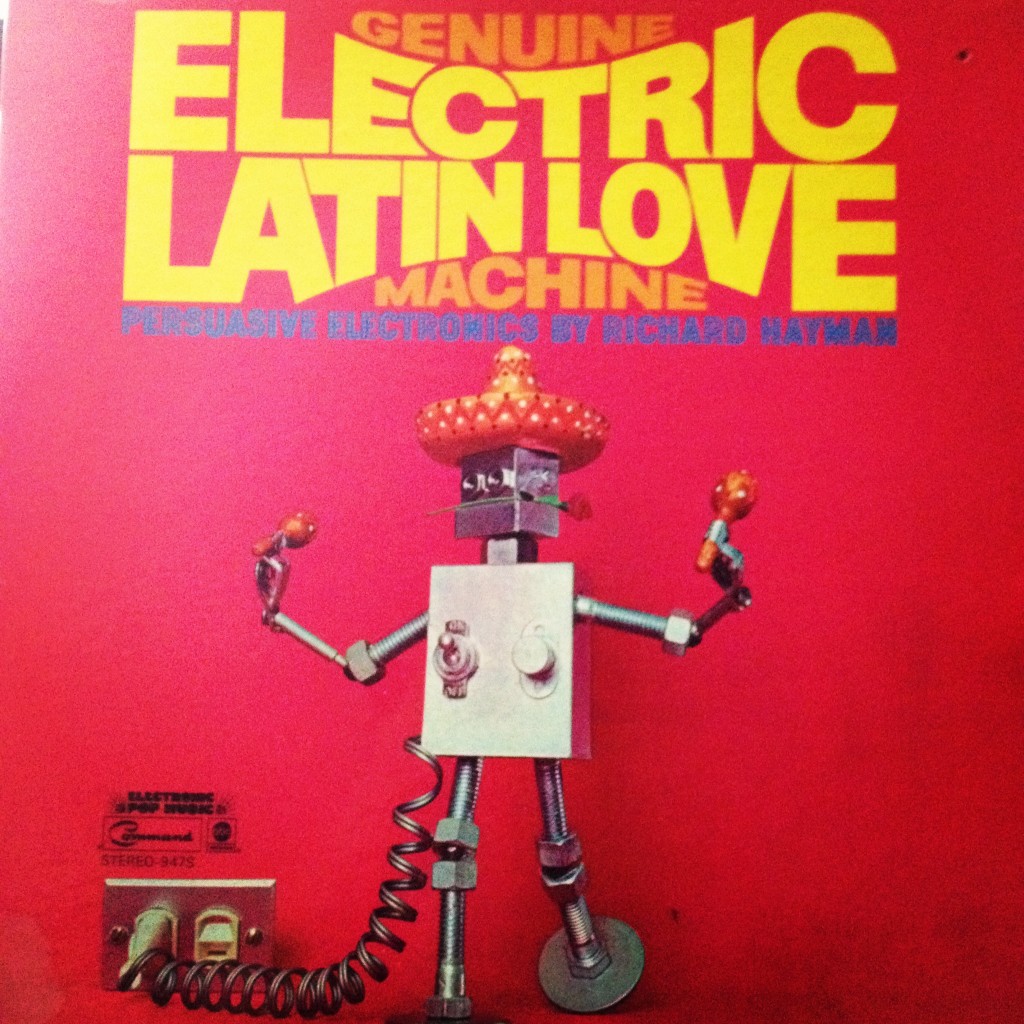

Switched-On Rock

Spinning Wheel

Jumpin’ Jack Flash

The 59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin’ Groovy)

Get Back

Yummy Yummy Yummy

The Weight

Time Of The Season

Aquarius/Let The Sunshine In

You Keep Me Hangin’ On

Hey Jude

Switched-On Rock is an all-Moog covers album, one in a long line that came out in the late 60s and early 70s to capitalize on the surprise runaway success of Wendy Carlos’ Switched-On Bach, the first of its breed. It’s a cash grab, no doubt about it, but it’s a relatively decent cash grab that was obviously made by people with some recording knowledge.

The album was produced by one Norman Dolph. And if you read this blog or follow Velvet Underground news at all, then that name probably sounds familiar. Dolph was an executive at Columbia Records in the 60s and 70s who funded the recording of The Velvet Underground and Nico in 1967. He also served as an uncredited engineer on the album, and it was his test acetate of an early version of the album that found its way onto eBay and eventually into the hands of a collector for the price of $25,200 back in 2006.

It seems like this record was a passion project for Dolph, as not only did he work as the album’s producer and “big twiddler” (that’s the credit he has) but he also wrote the majority of the album’s lengthy liner notes, which I’ve transcribed for you below. Â They’re a fascinating glimpse not only into the shockingly complicated recording process (Moogs could only play one note at a time, meaning that many overdubs were needed), but also into the popular views of what electronic music was at the time. Dolph makes sure to go out of his way to explain that these aren’t the creation of some computer, that a group of people actually worked on these compositions.

Download and enjoy the groovy instrumental Moogsrumations (yeah, I made that word up, so what?), and be sure to read these liner notes, they’re something else.

Because I thought up the basic idea for this album (and then contributed little else), I was thrown the bone of writing the liner notes. To give me something to work from, I asked Norman Dolph, the album’s producer, to send me a memo on the subject. The result was so much better and more understandable than anything I could have written that it is simply reproduced below.

Cordially, Russ Barnard

LINER STUFF

I’ll just sit here at the typewriter and spew out odds and ends about the project and let the literary maven sit it right.To begin, we are a triumvirate: Kenny does all the keyboard work, Alan writes the arrangements, and I tune the machine and perform sundry A&R functions.

The amazing thing about all the sounds is not that they are done one voice at a time, but rather one finger at a time. The silly machine only plays one note at a time and the temptation to play a chord must be overcome…you only get the lowest note if you press more than one key. Improvisation is difficult but far from impossible if you redefine the problem.

We, being faced with the limitations of the Moog as far as chords are concerned, built a gadget called the Protorooter that structures chords above the note the keyboard is playing to alleviate the problem somewhat.

Compared with the old cut-and-splice way of making electronic music, the Moog is a tune boon. As great as we feel the Moog is for making music in the light of what is possible and what Mr. Moog is no doubt cooking up, the Moogs of today are like the Kon Tiki. It takes quite a bit of physical tuning and set-up time to achieve the sounds, though once tuned they go down very quickly.

After kicking the project around in our heads and experimenting, Alan decided to look at the problem as one of orchestration, writing from scratch as though any instrumental texture available or conceivable existed – and then we set about to tune the machine to fit the arrangement.

The charts are such that if acoustic instruments existed to create the sounds, then live men could perform the record as such.

Likewise, we worked all ten tunes at once so that a tuning economy could be effected; e.g., tuning up a basically brass sound and then touching it up for various parts in a couple of songs.

By working on all of them at once we also could take advantage of any auspicious accidents that generated a sound that we had not conceived exactly but had a spot for.

There are hundreds of dials and jacks on the machine and many of the sounds are quite hair-trigger and difficult to re-recreate. Copious were the notes taken of these sounds, but when we found a screaming nugget of sound, we used it where it fit and then went back to the agenda.

One thing that must be stressed: namely, is that this record is virtually 100& Moog – only two instruments are live. One is the drum set; Moog drums are possible, but, in this stage of the art, sound kind of mechanical and ricky-tick…we decided to preserve the firepower in the music by moving it along with real drums. Leon Rix joined us on drums…very tasty. The second real sound we leave to the listener is to spot. We defy him to do so, and welcome his guesses.

This is a synthesized record. All the orchestral textures, somewhere in the vicinity of 150 different varieties, come out of that funnybox.

The semantics of keeping track of the sound from a bookkeeping point of view were kind of testy in that many of the sounds have no natural counterparts, so we coined neo-names to enable communication: e.g., the Gworgan, which is like a Gwiped organ. Gwiping is the act of sweeping a filter with a high regeneration setting (whatever that means) from top to bottom. It makes the sound “gwirp” with millions of variations depending on the rest of the brew. The inverse is Pwee, sweeping from bottom to top.

The Pagwipe sounds like a ferocious, leaky bagpipe.

The Jivehive sounds like a megaton of bees all swarming in tune. And there is the dread Moogoboe. And the Sweetswoop, a back and forth roar of harmonic sounds like a jet plan flying through your head. Other parts were named by their function in the song…the Octangle, an 8-part progression…the Big-Band, the Neoturnsolo, the Dharmilt, a mixture of descending harmonies and a sound that reminds you of a little three-inch-high Milt Jackson playing an equivalent size vibraharp: the thumps, the buzz, the telegraph keys.

In addition, many, many straight instruments: trombones, trumpets, flutes, basses, strings, drums, clarinets, bassoons, bass clarinets, tubas, clarinets, saxes, harps, electric pianos, harpsichords, organs, piccolos, ocarinas and recorders.

About half and half recognizable textures and totally new musical texturues.

No gimmicks though for their own sake, no one-shot gags.

We used a sixteen-track recorder for the job, making several passes, and then a demi-mix to boiled down the results to one track or a stereo pair. The results were parked and then the tracks used over.

Every time the engineer cleaned the tape heads I kept thinking that that’s my music you’re scraping off.

The stereo possibilities are remarkable in that there is no leakage from one side to the other, the sound is quite transparent and the listener can listen through the many layers and focus on whatever he wishes.

One thing to stress to thos unfamiliar with the way the m achine works is that it is not a computer and does not play or tune itself. In fact, having lived with it, we are as conscious of what it won’t do as what it is capable of.

For one thing, constant touch-ups of the tuning is necessary to correct its drifts over a fifteen-minute period.

Moog himself is quite a guy too. Most cooperative and now has a weekly emissary to New York to touch up any fixits and keep everyone up on the new discoveries. Moog really made quite an invention – and how appropriately space-age his name is! How bland would be the “Jones” or the “Irving Spidorsha” as a nickname for the gadget. If he ever comes to town for a lecture, go listen. There is nothing like inventing a synthesizer to give you expertise in its use.

Anyway, the music is human music, and, most important, it is music, not Moog effects.

This album is supposed to be a chuckle. Make sure you convey that we hope the people enjoy it!

All best,

Norman